The topic of classic banjo recordings from the early 1900s came up recently as a customer called a few weeks ago asking what banjo he should buy that would help him recreate the sound of that era.

He asked about the Vega #2 banjo since it has a Tubaphone tone ring which was invented in 1910. He asked about a Vega Senator which has a light brass tone ring. He wondered if the Vega Little Wonder was more “authentic” because it has the head stretched over the wood rim.

His questions came at me so fast I couldn’t answer each one as quickly as he was asking them. After we talked for a while, I managed to share some technical information which helped him understand better what he was really looking for.

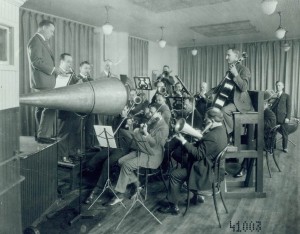

Recording equipment was just being developed in the early 1900’s. Early recorders were not able to record a very wide frequency range. This basically meant that the sounds that were recorded could not reproduce the broad spectrum of sound that modern recording equipment will do. Sound techs have referred to this phenomenon as “compressed sound”. This is why recordings sounded thin, without much bass, and without a lot of treble brilliance.

Recording equipment was just being developed in the early 1900’s. Early recorders were not able to record a very wide frequency range. This basically meant that the sounds that were recorded could not reproduce the broad spectrum of sound that modern recording equipment will do. Sound techs have referred to this phenomenon as “compressed sound”. This is why recordings sounded thin, without much bass, and without a lot of treble brilliance.

Because the banjo was a popular instrument around that time, it was natural for sound engineers to invite artists of the day to come in and record. However, the recording equipment could not capture the real tone of the instruments.

So, for us today to want to imitate this sound is not as much a factor of the instruments we play, as much as it is a factor of the recording we are listing to.

The high quality banjos from the turn of the 20th century were beautiful instruments. The few that I have played sounded nothing like the early recordings. While they didn’t sound quite the same as our modern banjos, they were NOT the compressed, plunky sound that is prominent on the early recordings.

I was once able to play an old fretless banjo from the 1870’s with calfskin head, scooped neck etc. And even that lovely old instrument was not the compressed, thin sounding banjo of the early recordings. In fact, it was rich, warm, and vibrant with good brightness and sustained beautifully.

The nature of a good banjo is lively, bright and sparkling. Plastic heads have added to the brightness of modern banjos, but a well tuned up banjo with a calf skin head, does NOT sound like an early recording.

Even the late great Earl Scruggs loved the tone of a calf skin head. But the practicality of the plastic heads appealed to him more.

After all, it was the original banjos that inspired our modern day banjos just as pre Stradivarius violins inspired the famous European violin makers. So while new banjos have some improvements over the original instruments, the old instruments are what drew us all to the banjo. If the old banjos really sounded like the old recordings, the modern banjos would sound more like the old banjos.

Also, early recordings of opera singers like Caruso, had the same compressed thin sound. If Caruso sounded like his recordings, he would have never made it on the opera stage.

The early recordings affected all instruments the same. Pianos, violins, voices and orchestras were all thin, compressed versions of the real sound. While we can learn from the performances on these old recordings, the tone we are hearing is not real. It is compressed due to primitive recording technology.

A city born fellow I know went to an old time music festival in West Virginia with his open back banjo to learn the traditional styles of the Appalachian mountain banjo and its techniques. He told me he was shocked to see many, and possibly a majority of old time players, with “bluegrass style resonator banjos” playing old time music. He said these people bought the best banjos they could afford whether it had a resonator or tone ring etc. Most of the folks there were not wealthy. They were folks that lived in the mountains and many lived in small log cabins and farmed or prospected or lived in small communities tucked away up in the mountains.

He also said that every “big city picker”, himself included, brought an open back banjo and had stuffed a rag under the head of the banjo to take out some of the brightness and sustain similar to what they thought was in the banjos from the old recordings.

I know that many old time players enjoy rolling up a small towel or sponge and tucking it under the banjo head to dampen some of the sustain and brightness and I am not making an argument against doing this from a musical point of view. However, at the festival my friend attended, the local players did not do this. They let their banjos ring out with as much volume, brilliance and sparkle as they could get. They were not imitating old recordings. They were making music with the most brilliant banjos they could afford.

He also said many of them had their banjo heads tightened up pretty tight and they used the standard top frosted head that came on the banjo. This is more of a traditional “bluegrass” banjo set up.

This story interested me because having grown up in the city myself, I also thought that traditional players played open back banjos for some kind of tone reason, etc. But from what I can tell, the players from the northeastern U.S. cities are the ones who adopted the “open back for old time music” standard that many of us now assume was an old tradition.

It looks to me, like the players in the early days of recording were just as interested in a vibrant, bright, and brilliant banjo as today’s players. They valued the clarity, brilliance, volume and responsiveness that many “bluegrass players” look for in their banjos today. They played the banjos that were available to them at that time in banjo history, and many of these banjos created a precedent of what is desired in today’s banjos.

It was just a fact of life back then that the recording technology of the day really could not capture the tone of a fine instrument. But that didn’t stop the early players from buying the most brilliant sounding banjo possible. During the early days of recording, equipment that today is considered primitive to the point of useless was state of the art. The fine banjos during the early days of recording however, are still considered to be fine banjos; but they don’t sound like the early recordings.

If you are thinking about learning some of the old music from early 20th century recordings, remember that the notes and chords are what you can learn. The tone of the banjos is harder to discern because of the limitations in the early recordings.

Also, that compressed sound is not what those artists were trying to accomplish. That sound was the limitation of their technology. The banjo’s tone and the recording of the tone are completely separate phenomenon.

While there are discussions today about getting the best tone from a banjo or other instrument in today’s recording technology, the recording equipment today produces far more “real” banjo tone when engineered by a skilled set of hands and ears.

So, learn the music, and enjoy the real tone of a good banjo. Remember that the old banjos didn’t sound like the old recordings, and you’ll enjoy learning those beautiful old songs even more.

If you’re shopping for a new banjo to play old music from the classic banjo recordings, remember recorded sound is not live sound.

It is generally accepted that the first banjos were constructed without a tone ring. They were built with a round rim made of wood with a skin head (just like...

When we receive a call from a customer who is interested in “old time banjo” this raises a few questions. Does "old time banjo” mean pre-Civil War? Does it...

One question I hear a lot is "what is a banjitar?"While I have dedicated years pointing out that in fact it is called a 6 string banjo, many folks dismiss the...

If I told you that banjos were good for your health what would you say? We are told today that a return to the use of natural/organic products is good for our...

3733 Kenora Dr.

Spring Valley, CA 91977

COMMENTS